Too many staff in NT public schools are employed on contracts, writes Branch President Jarvis Ryan. It’s unfair on staff and is hurting the NT’s ability to attract the best teachers from interstate.

Before I came to teach in the Territory, I vividly remember attending an impressive seminar at the swanky Sir Stamford Hotel at Sydney’s Circular Quay. A young teacher spoke passionately about his experiences teaching in a remote community.

Seminars like this took place in several major cities around Australia. They were advertised in the big papers and were a recruitment push by the NT Department of Education to attract adventurous and talented teachers from around the country.

Later, I was interviewed at another swanky hotel by a panel of three DoE officers to be assessed for suitability.

I’m sure many of you teaching in the Territory had a similar experience. For a long time, the NT DoE made a strong push to recruit from interstate, and central to the marketing pitch was the lure of permanent employment.

Most of those who commenced teaching in the Territory before 2013 describe being offered permanency within two years.

But everywhere I go when I visit schools all over the NT today, I meet disgruntled teachers who describe having been on a series of fixed-term contracts for three or four years and sometimes even longer.

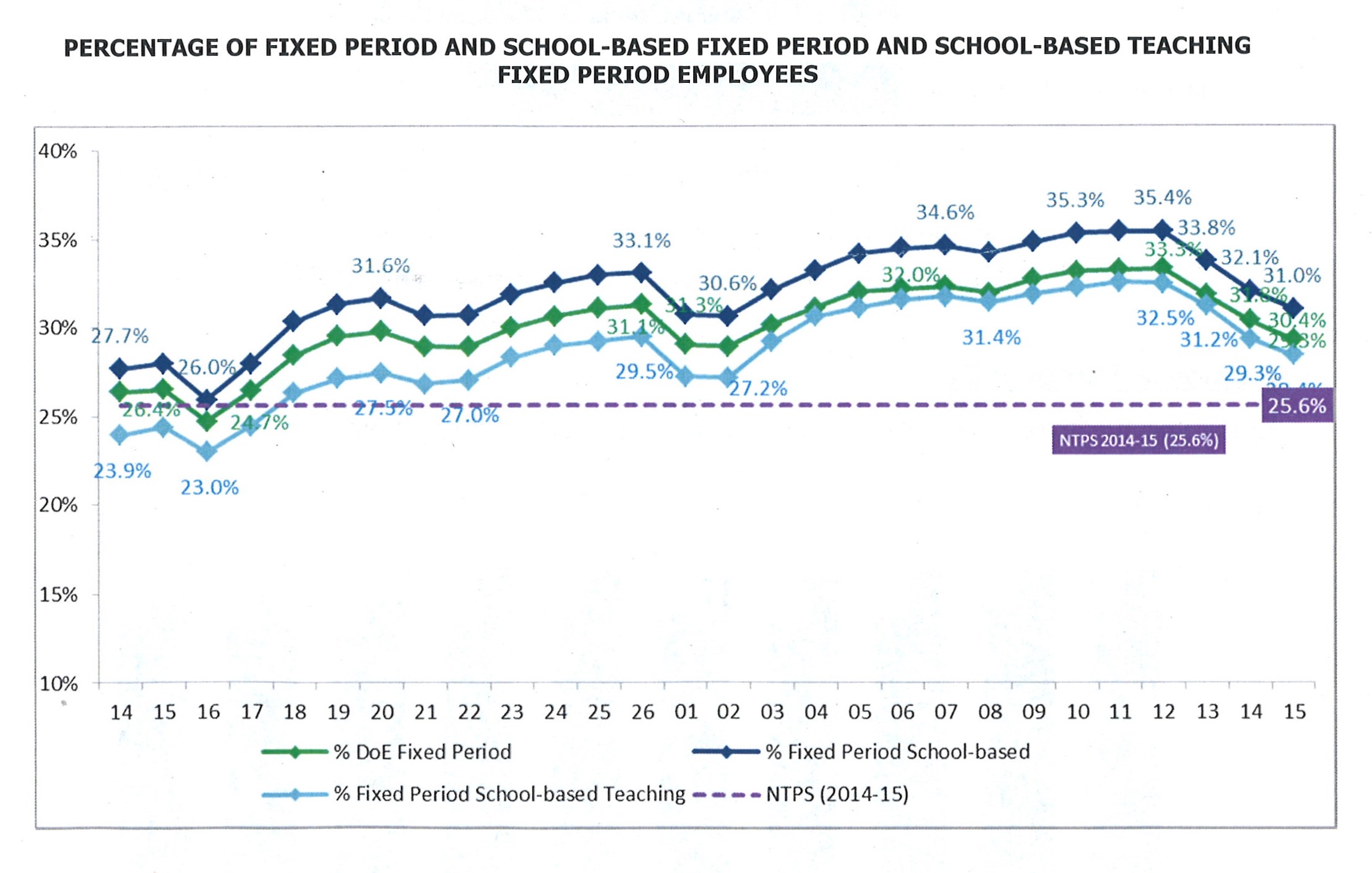

Since 2013, which saw the last big conversion of staff to permanent status, the proportion of teachers on contracts has soared, from 13 per cent to well over 30 per cent (see the graph below*). The situation is even worse for non-teaching staff.

* NOTE ON GRAPH: This graph covers the period from the beginning of the 2015 school year until early in 2016. The figures make it look like the level of contract employment has declined in recent months. This is only due to contracts ending over the Christmas holiday period. There has been a steady trend in the growth of contract employment since 2013.

To try to break the impasse, in 2014 the union agreed during enterprise bargaining negotiations to support the introduction of school-based merit selection procedures for the appointment of classroom teachers.

The Department was keen to align staffing selection with its push for devolution, or Increasing School Autonomy, as it is badged, and also the merit principle, which is supposed to underpin all permanent appointments in the NT public sector.

The union agreed to the changes but also signed a memorandum with the Department agreeing that an overall target of 85 per cent of agency staff in permanent employment was both realistic and desirable, and that both parties would work co-operatively to achieve this figure.

I have no hesitation in saying that the new policy has been a dismal failure. According to figures provided by Human Resources, since the memorandum in late 2014 only 130 permanent positions have been offered, of which only 84 were for teachers. This is far less than the number of permanent staff who have resigned or retired in this period.

In my view, the major culprit is clearly the Global Funding model (also known as global school budgets). With all permanent staff now required to be “attached” to a school, the impetus to offer permanency has to come from principals. Their failure to offer many positions demonstrates nervousness about the impact appointing permanent staff will have on their budget, as the salary cost of nearly every staff member now has to be factored into the school’s operating budget.

Merit selection means the best candidate should get the job, regardless of how much they cost. But many principals seem concerned about employing CT9s when they may only be able to cover a CT3 in their budget.

This dilemma is central to why the AEU views Global Funding as a disaster and we will continue to lobby for its rollback and dismantling, or at the very least the removal of most of the staffing costs from school budgets.

The current model imposes too much risk on individual schools, especially in an environment in which schools budgets have been frozen or cut in real terms. It abrogates the Department’s responsibility as the overarching employer to strategically manage its overall workforce profile, including staffing costs.

Not only is the current stasis unfair to staff who have been on contracts for several years, it means the NT is missing out on attracting many of the best teachers from interstate. As a very small jurisdiction which only trains a fraction of its own teachers, the NT will always be overwhelmingly reliant on enticing teachers to move from other states. The AEU’s view is that a strong incentive program with realistic prospects of permanency is vital to attracting and retaining high-quality teachers from interstate.

Principals are currently largely left to do their own recruiting, and a number have spoken with me about the difficulty of finding suitable applicants.

Clearly we need to create a better balance between local selection and centralised workforce planning.

The union has flagged our concerns on numerous occasions with the Chief Executive, Ken Davies, who has acknowledged the high level of contract employment is a major problem. Mr Davies told a meeting of school leaders during the mid-semester break that if principals didn’t move on this issue, he would, and impose solutions from above. He signalled a readiness to work with the union to find solutions, and indicated the Department would soon commence interstate recruitment again.

One idea I’ve floated with members that seems popular is offering permanency within a region. Staff might not be guaranteed ongoing employment in their school of choice, but would have greater certainty. But for this to work we will need to work out an appointment process.

I can assure all members that the union will make the issue of permanent employment a core priority in the coming months, and especially as we get prepared for enterprise bargaining next year.