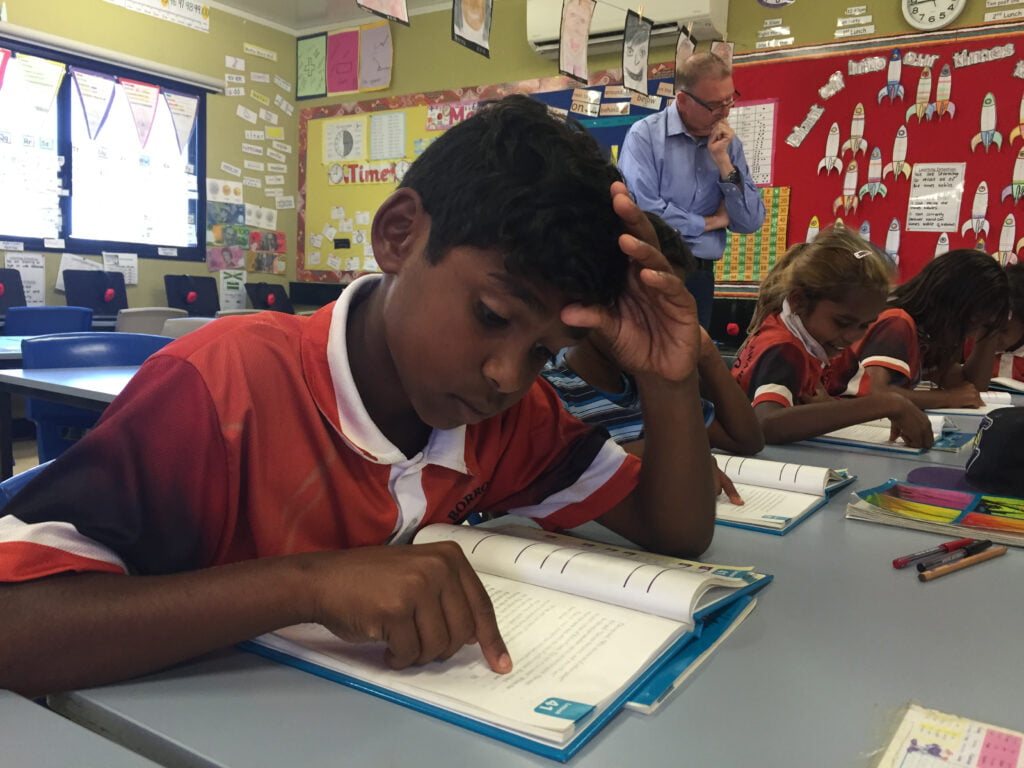

Former Education Minister Peter Chandler observes students at Borroloola School doing Direct Instruction learning activities Photo: AAP/Neda Vanovac

John Guenther is a senior researcher at the Batchelor Institute who recently co-authored a paper in The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education evaluating the impact of the Direct Instruction (DI) program in remote schools. He spoke to Jarvis Ryan about his findings and what they reveal about problems in how governments approach Indigenous education.

Could you firstly explain the methodology you used to conduct your research into the DI program?

We used data from the My School website that anyone can access. For this study, I looked at the schools that were identified as Direct Instruction schools through the Flexible Literacy for Remote Primary Schools program that was funded by the Australian Government with about $30 million.

I looked at the schools classified as “very remote” on My School. They are the ones that struggle the most, particularly those very remote schools that have lots of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. I wanted to see whether or not the introduction of Direct Instruction in some of those schools led to those students doing any better, or similar or worse than schools with a similar student cohort where they hadn’t received that intervention.

I looked at the data three years before the Intervention (2012-2014) and three years after DI was introduced (2015-2017). What I tried to do was establish if the schools that received the Direct Instruction intervention had an improvement in literacy.

I am also aware that there are shifts and patterns over time in the general school population so I wanted to see how comparable schools that didn’t receive that intervention fared over that period.

The important thing here is that you had reasonable sample sizes and you were as far as possible comparing like with like.

That’s right – that’s why I limited my study to those schools that had more than 80% Aboriginal kids in their student population and only in very remote schools. We are not comparing schools that were in more urban areas which had fewer Aboriginal kids.

In the cohort of the Direct Instruction schools there were about 25 we could have chosen from, but not all those schools had NAPLAN scores published, so we had a sample of 18 DI schools. That was enough to do an analysis.

You focused your study just on the reading component of literacy in Direct Instruction. What did you find in terms of its impact over those three years?

I chose reading because it is a measure used by other national reports, and governments tend to take a view that reading is a good proxy for English literacy generally.

What we found was the schools with DI intervention actually did worse post-2015 compared to the 2012-2014 period and worse overall than the non-DI comparison schools. That is a worry for a few reasons. Firstly, because this program was funded significantly by government and then renewed even though the early signs were that it didn’t work, so there is an accountability issue.

The second concern is that you are putting money into a program that is doing harm to kids, it is not actually benefitting them. Not only did DI not achieve its goals of improved literacy, but the outcomes from the schools involved were worse than the comparative schools.

The third finding is also worrying: schools with a DI intervention had a faster rate of decline in attendance than the comparison schools. Average attendance declined quite rapidly for the DI schools. The earlier evaluations treated poor attendance as a factor that contributed to outcomes, but I am not sure that is necessarily right. I think it is more likely the other way around, that because of Direct Instruction and what it does in the classroom, and what it does to the kids, they are less likely to want to attend and their parents probably see that as well.

There were a whole lot of worries that weren’t captured in the evaluation report, and that needed to be addressed. To be honest, after the first round of funding that was effectively a trial for two years, the program should have been stopped. It wasn’t achieving results then.

The attendance issue is really telling. We had many stories about kids getting bored of the program quickly and as you reference in your paper it appears many teachers also got bored of the program. From what I have observed based on the knowledge and experience of AEU NT members, in many of the DI schools we saw close to a turnover of 100% of teaching staff over the three-year period.

I think it is something about the method that is fundamentally flawed, not just the intervention or a program. It dumbs down teaching so that everything has to be to the formula, you have to follow the script all the time and that takes away the teacher’s professional ability to be able to respond to where their class is at, where the individual children are at and work with them at a student level, not just for a program.

That is possibly what is going on with the teachers getting disenchanted with it, because it takes away their professional ability, their pride and their ability to do what is best for their children and their class. It leaves it up to a scripted program.

I want to end on a slightly more positive note. I picked up in your writing that there is not a lot of evidence to support these silver bullet-type ideas of a magical pedagogy or program. You make some reference in your paper to evidence-based approaches to improving outcomes in remote schools. What kinds of things can we draw on into the future to build a stronger foundation?

Teachers who can teach English as a second or other language will do better in the classroom. It is not necessarily an argument about bilingual versus non-bilingual approaches, it is an argument about the importance of professional development and learning for teachers.

You can’t just run a program for one year and hope that it is going to have an impact for five years. Every year you have got to run these programs to build the professional capacity of teachers. When education departments run professional learning for teachers will benefit from it and the kids will benefit from it.

Another key area where the evidence is pretty clear is that schools with higher proportions of local people on staff do better in terms of attendance and NAPLAN scores. It is heartening to see that the non-government sector has picked up on this. The trend in recent years, again using My School as an indication, is that non-government schools, particularly in Western Australia and the NT are using the increasing resources that they are getting from the Federal Government to train and support local people into roles within the school.

Unfortunately, it hasn’t been taken up as much by the NT Department of Education in public schools. Part of the reason for that, in the Territory at least, is the role that “effective enrolment” has played – the funding model that reduces a school’s funding based on lower student attendance rates.

Schools with lower teacher-student ratios in remote areas do better than schools with higher teacher-student ratios. The claim that the student-teacher ratios make no difference is wrong. It does make a difference in remote schools at least.

One of the reasons I think is that it means kids can get more individual attention and that they have got a combination of small class sizes. With local support and local staff supporting them, they have got a much better chance of grabbing hold of the concepts being taught, the language being taught, and benefit from it.

So, there’s a few things that we do know work generally. Of course, it is not a one-size fits all. We have got to take each community on its own. But I think as a principle, having these factors in play, will make a difference to the learning that happens at school.

This article was first published in the Term 2, 2020 edition of the Territory Educator magazine.